GIRLFRIENDS WITH GUNS - Text by Marie Le Mounier - From the Self-portrait as a Drowned Man, by rebelling artist Hippolyte Bayard, to the carte-de-visite portraits people started exchanging in France and Europe towards the end of the 1850s, photography has trained its lens on and captured the individual from the very beginning. Autobiography, fiction, auto-fiction: photography allows human beings to show, narrate, and invent themselves; it gives them a way to satisfy the desire for recognition.

The photographic portrait—and, more specifically, the carte-de-visite portrait—announced the democratization of the representation of the self in the nineteenth century. The snapshots produced by the studios of the day for a public eager to fix its own image reflected a model that had been defined by the aristocracy. Fixed by the machine, the (rigid) poses, the (pompous) décor, and the (bourgeois) accessories were so many stereotyped elements that functioned as indexes for the sitter’s membership in a particular social class. According to Frizot, the infinitely reproducible carte-de-visite portrait accelerated the “flattening out of all the values in a society that favored mimetism.”1 These conformist and impersonal mise-en-scènes were above all the support of a social game. And, because use/use-value eclipsed form, their aesthetic quality was of little importance, since they essentially participated in a strategy for recognition within a system of codified exchanges.

Photography has only gained in popularity since the end of the 19th century. And if the perennial fluxes of fixed or moving images have in the intervening years conditioned how we perceive the world, they have also examined the most general problems of perception and representation. Thus, as D. H. Lawrence writes: “As vision developed towards the Kodak, man’s idea of himself developed towards the snapshot.”2 In the age of the cellphone and social media, photography is more than ever at the heart of social interactions. The “moment” may no longer be a “Kodak moment,” and images may indeed have lost their materiality to pixels. Still, they continue to bear witness to an individual and collective reality, they remains charged by norms and codes.

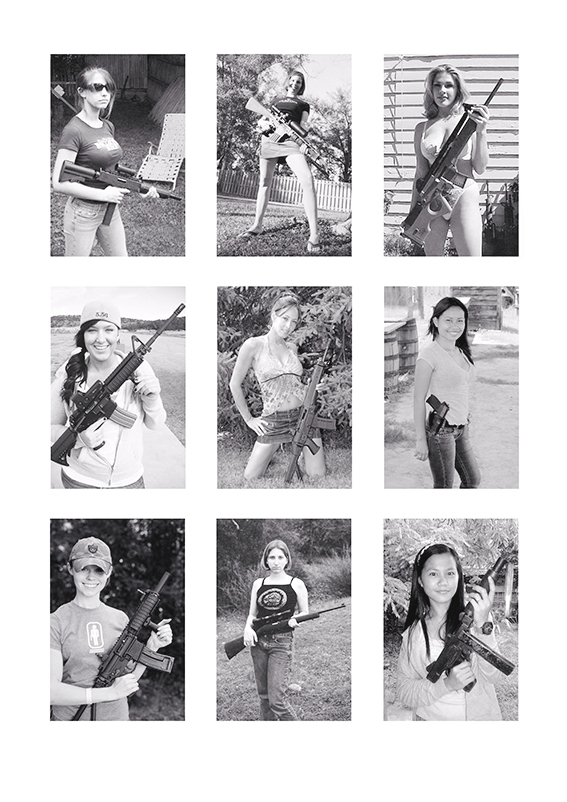

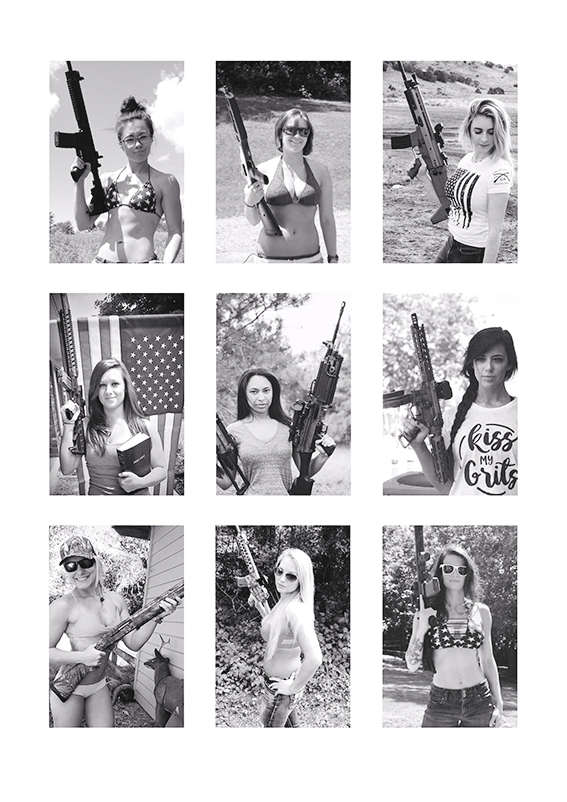

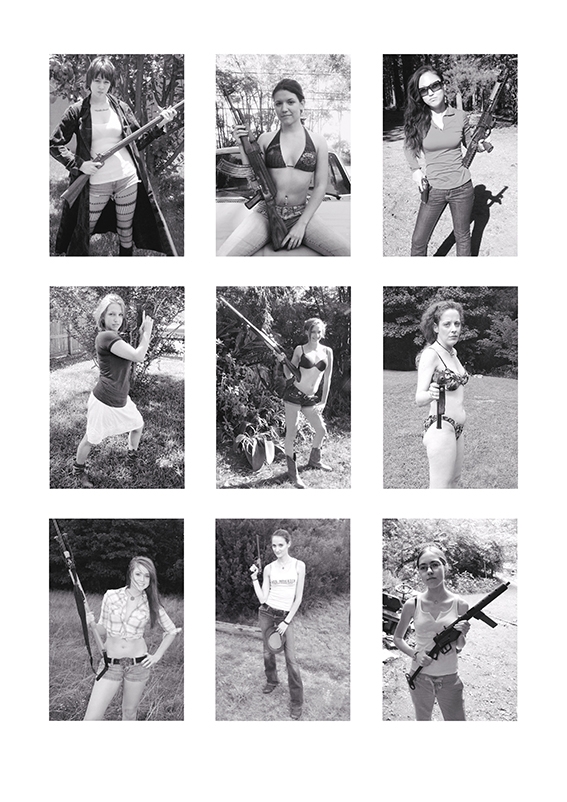

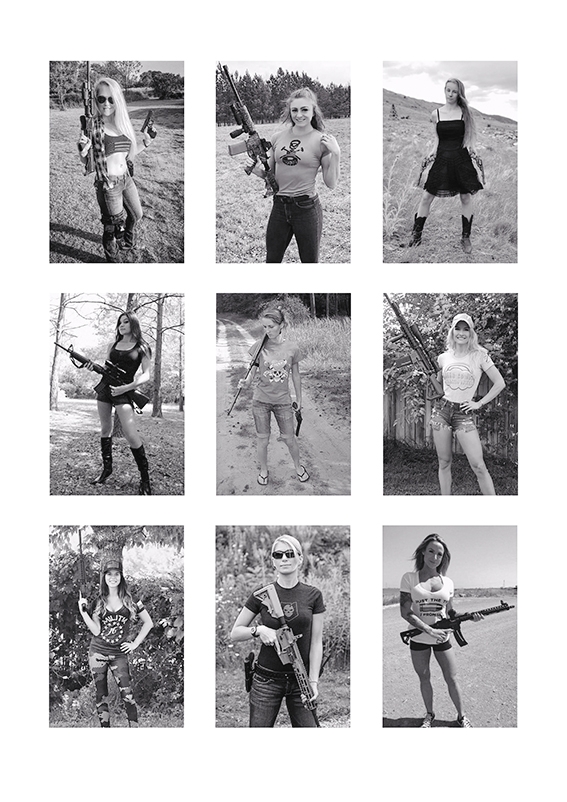

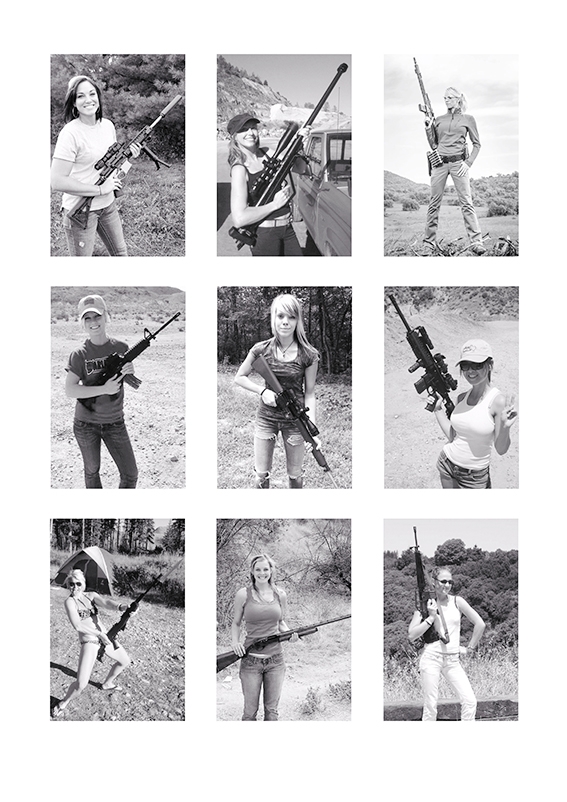

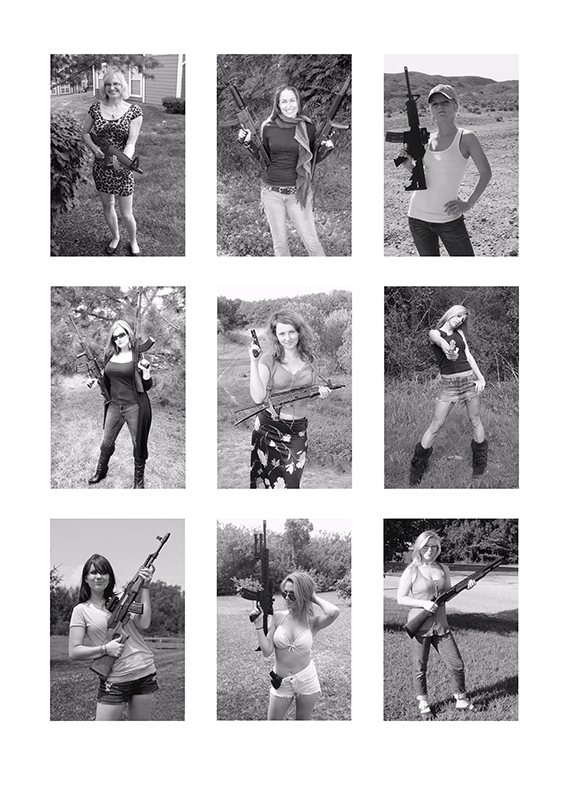

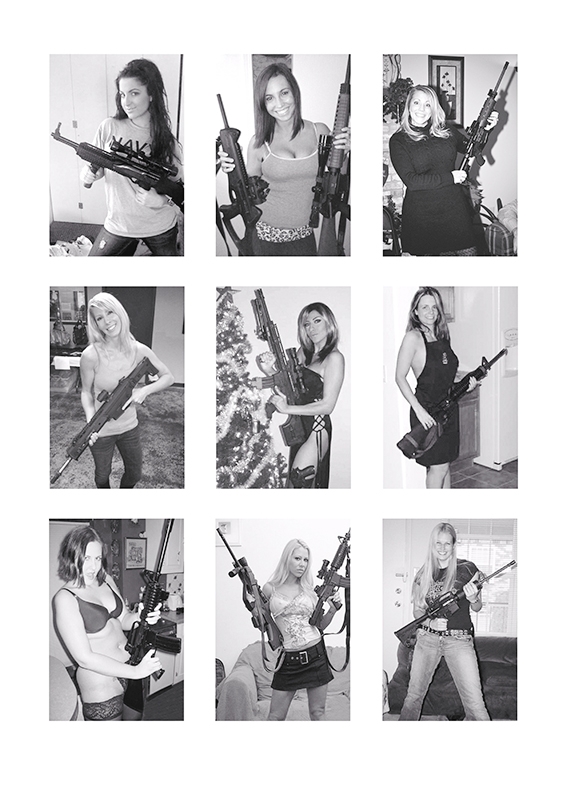

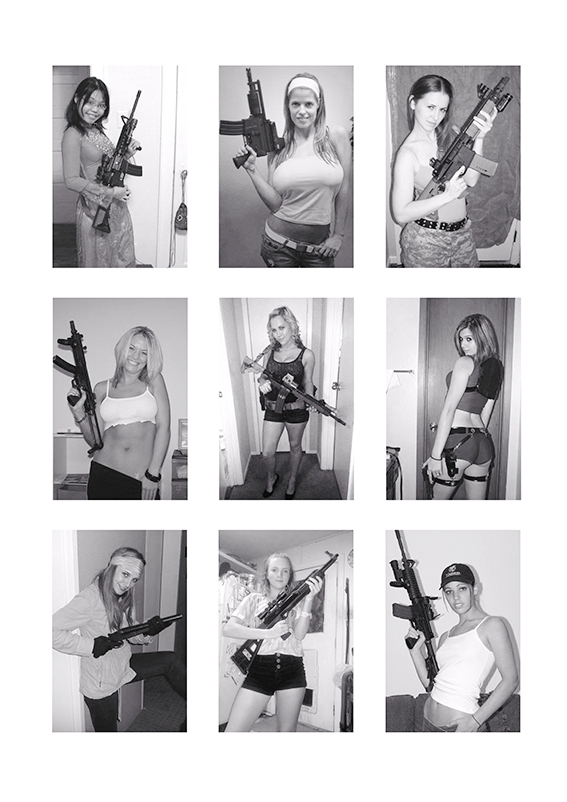

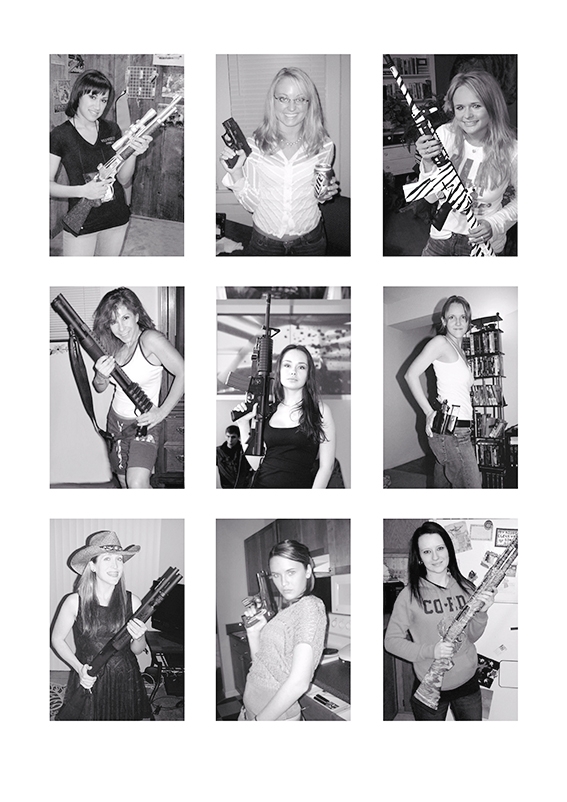

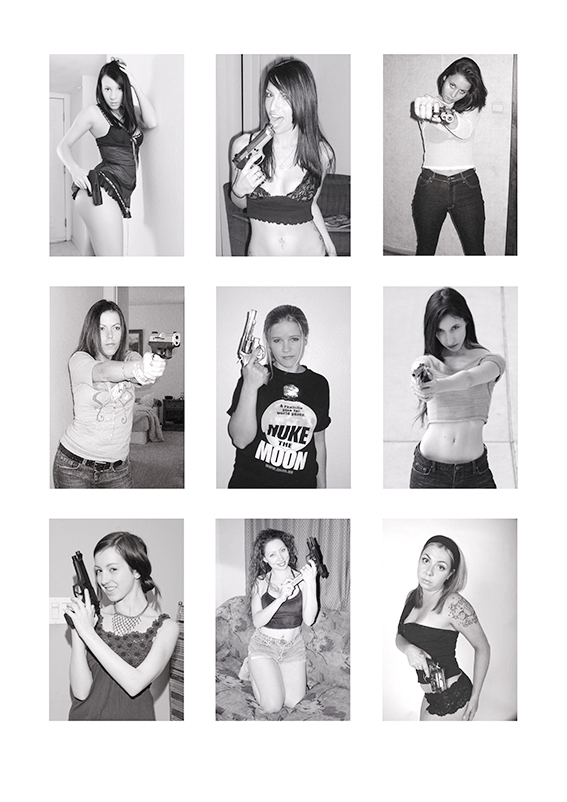

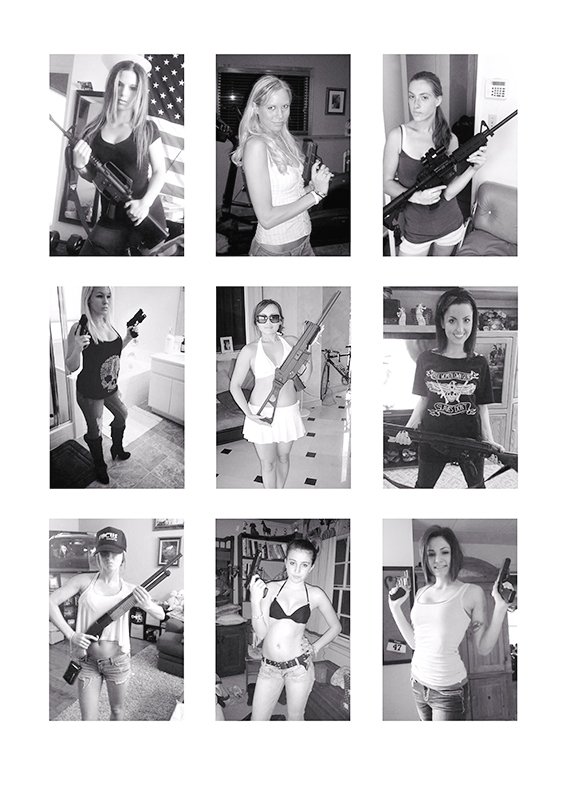

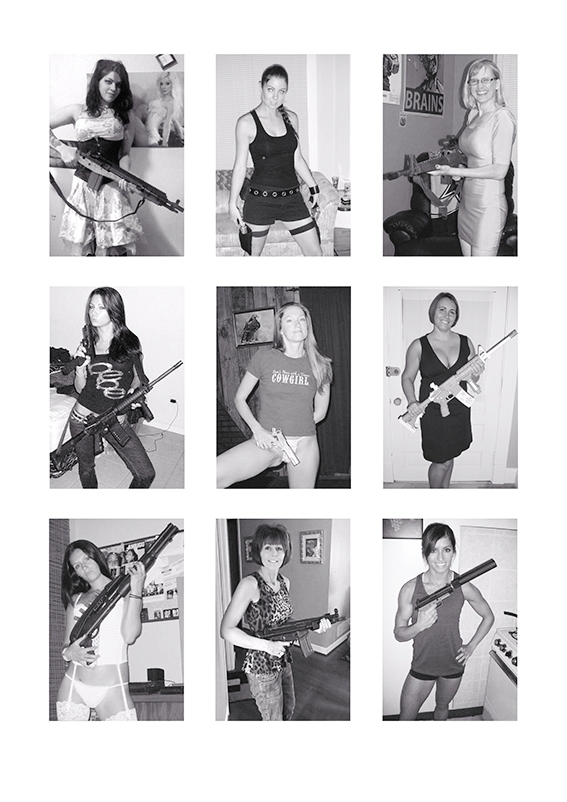

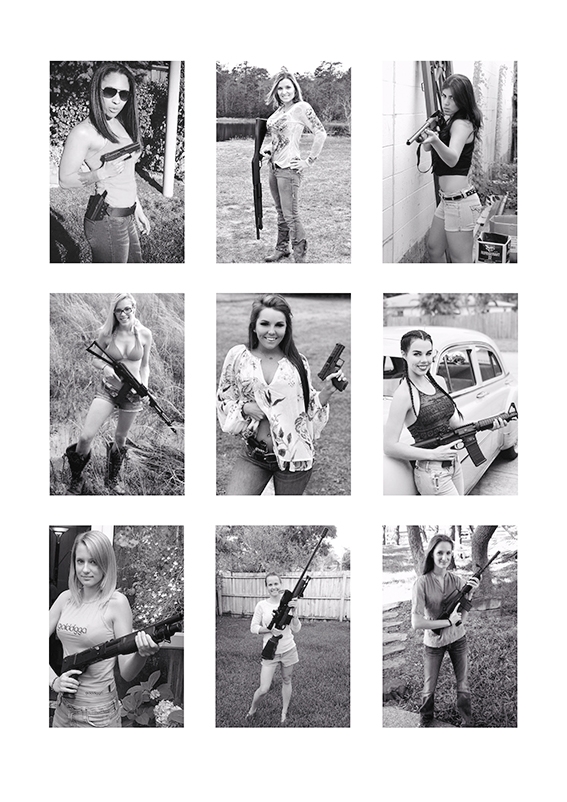

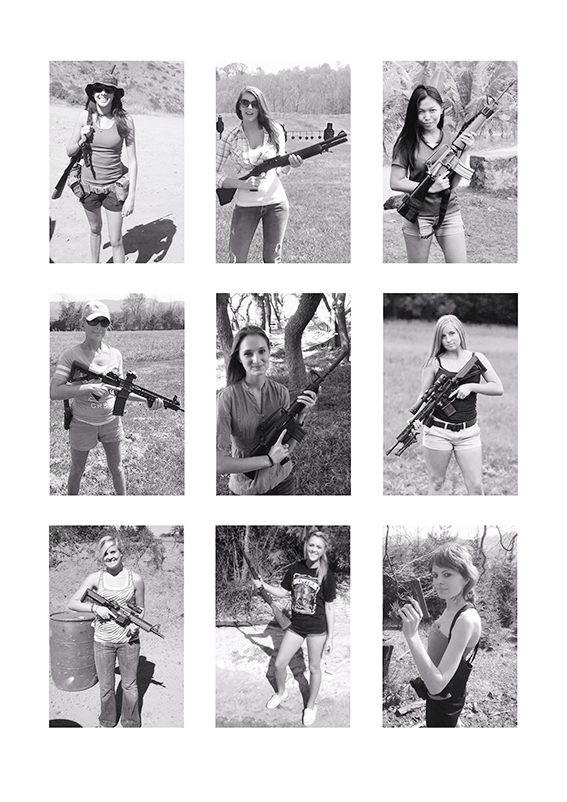

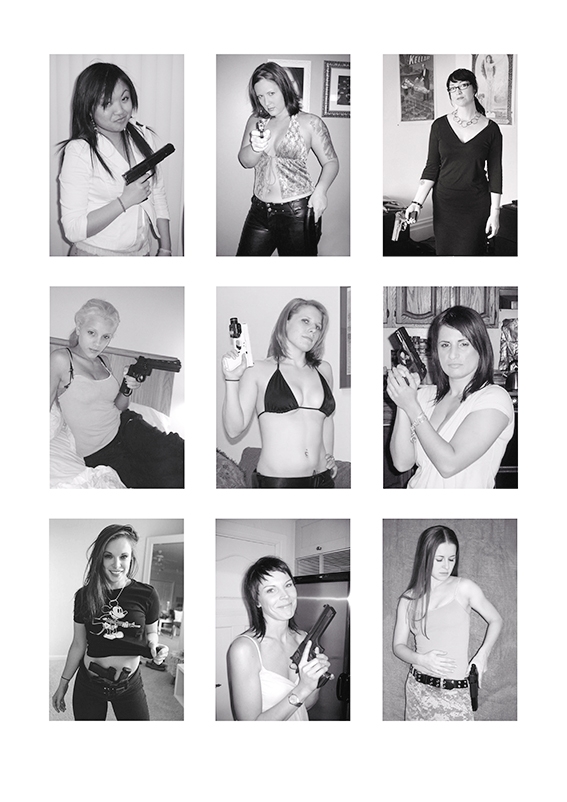

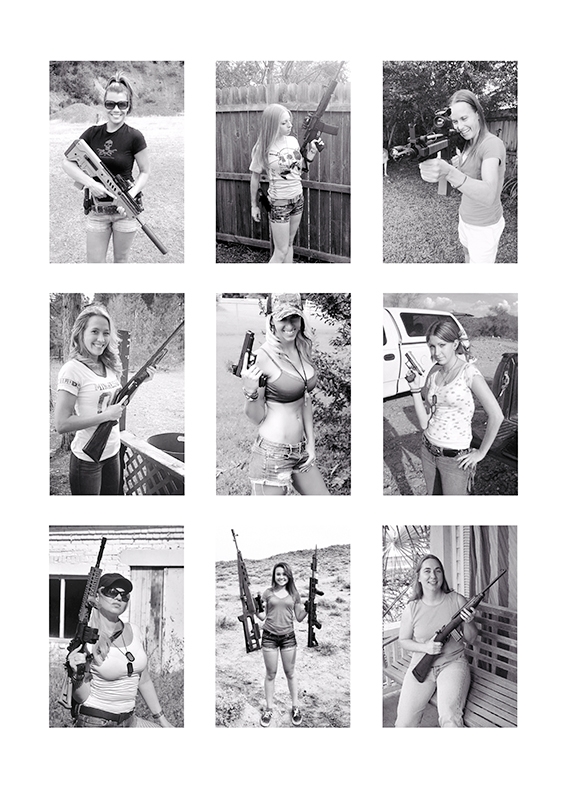

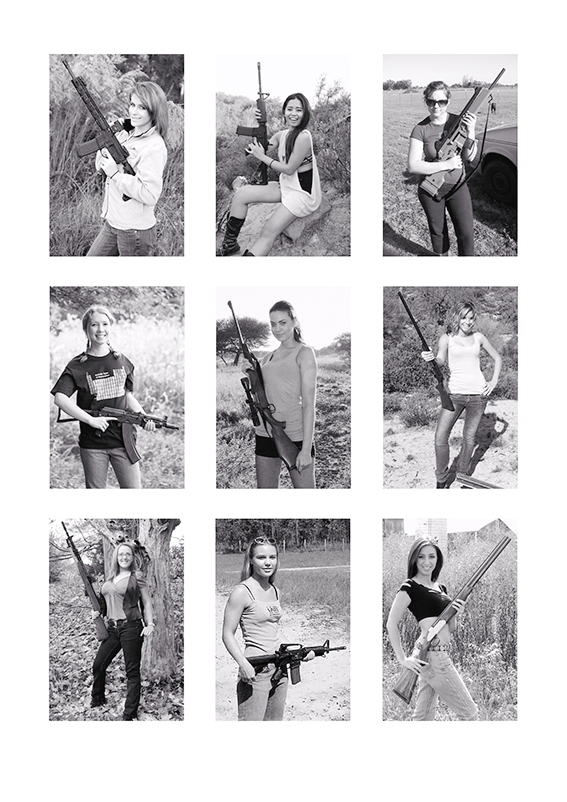

At the origin of the series, Girlfriends with Guns, are hundreds of snapshots exchanged on gun lovers’ forums and blogs. These ardent amateurs of all manner of handguns and rifles show off their girlfriends posing with a weapon, usually their own. Between porn star and film heroine, these “girls next door” assume a purely decorative function that showcases, first and foremost, the weapon they pose with, sometimes awkwardly. Although these images are taken with no artistic ambition whatsoever, they nevertheless borrow the aesthetic codes of cinema and advertising. Godard once said that “a girl and gun” is all one needs “to make a film,” and the same holds true here: a gun, a photographer, and a model who looks like she is relishing her part are the prerequisites for a good shot/for an effective image.

Arranged like a collection Girlfriends with Guns, like the carte-de-visite portraits, remind us of the value of social exchange but also of the importance of the construction of the projected image in a world where the border between self-perception and public image is increasingly blurry. Situated somewhere between personal history and mirror of the dominant aesthetic, these images have an utilitarian function: like a trophy, they telegraph the specific status of the person who posted them. In this context, can we say that the image narrates the subject, or a certain state of the world? That a photograph never attests to anything other than the trivial reality of the person who shot it? That to make an image, all you need is a cute girl, revealing clothes, and a gun? But perhaps what we should we say is that we are a composition between reality and fiction.

June 2019

English translation Emiliano Batista

Notes

1 FRIZOT Michel (dir.), Nouvelle histoire de la photographie, Paris, Bordas / Adam Biro, 1994.

2 LAWRENCE D.H, Eros et les chiens, Michel Bourgeois, Paris, 1969